Day 4 - Gwalior Fort

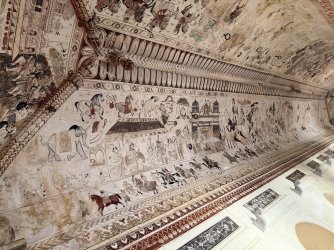

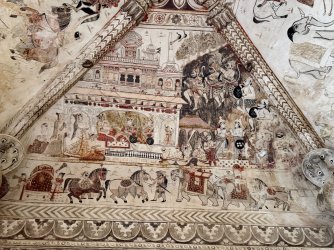

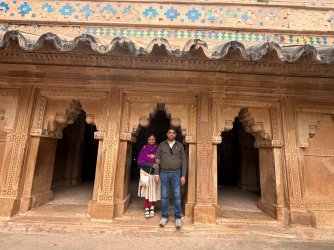

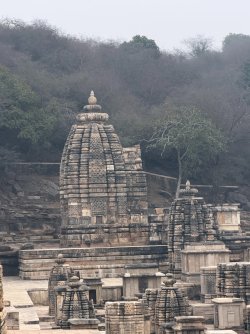

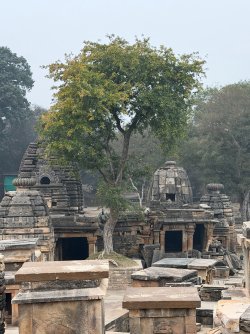

Gwalior Fort sits on a long basalt plateau above the city. The fortifications around the plateau are traditionally linked to Raja Sourya Sena, with the defensive circuit said to have been completed around 773 CE, and the site appears in old inscriptions under names like Gopachala and Gopagiri, “cowherds’ hill” in Sanskrit. Over the centuries it cycled through a who’s-who of North and Central Indian power, but its most decisive architectural makeover came under the Tomars (1398–1516), especially during the reign of Man Singh Tomar, when major palaces and additions turned the fort into a full royal city on a hill.

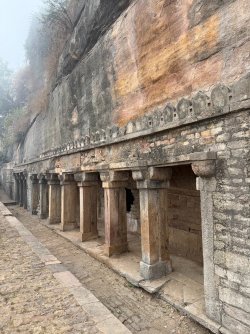

We reached early, around 7:30 am, and immediately discovered that the fort does not belong to tourists at that hour. It belongs to morning walkers, yoga practitioners, and cows on their morning strolls. We started the climb upwards against the flow of the early-morning exercise crowd in dense fog, which gave the whole approach a dramatic, cinematic effect, while also ensuring that clear photos were largely theoretical. The fog only began to lift around 11 am, when we were making our way down, at which point the fort finally revealed itself properly.

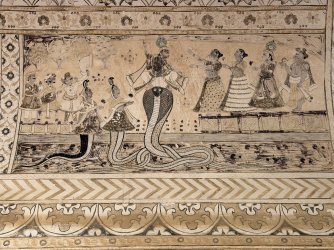

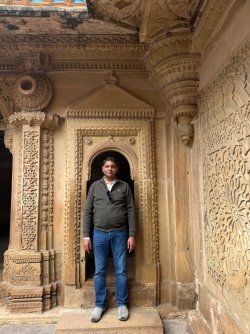

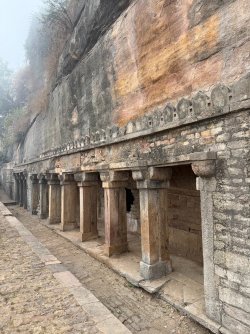

On the way up, you pass the 15th-century Jain rock-cut sculptures carved into the cliff face, immense figures emerging from the rock in a way that makes “carving” feel like an understatement. Midway through the climb there’s also a small, humble temple that many people simply walk past, despite signboards pointing it out. In a complex full of grandeur, it’s strangely easy to miss something quiet.

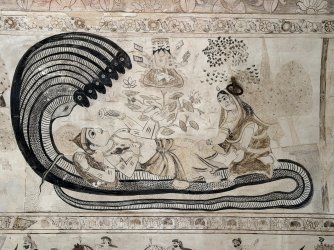

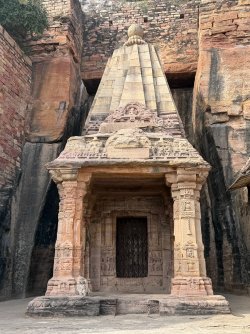

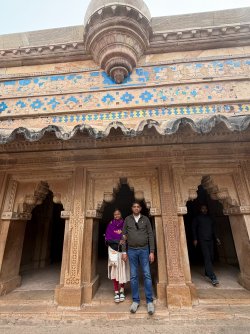

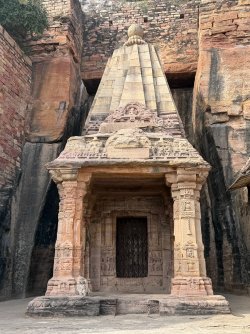

Chaturbhuj Temple

Chaturbhuj Temple

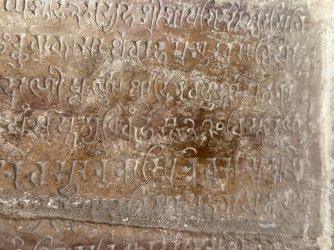

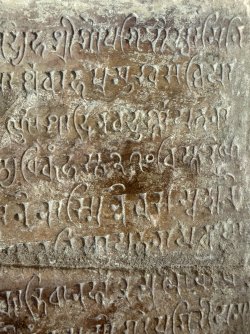

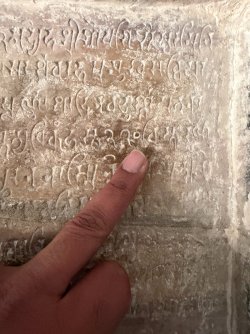

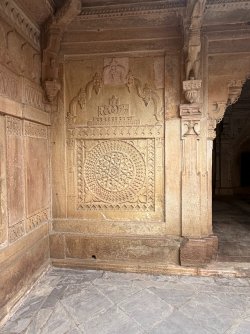

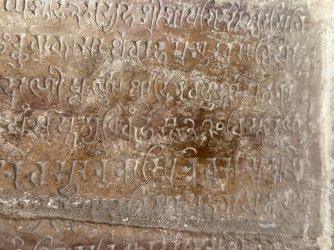

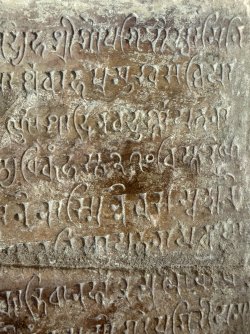

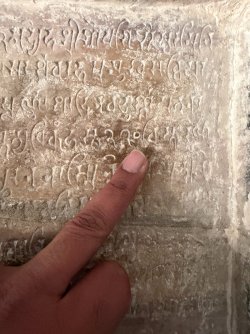

And then we reached the real target: the Chaturbhuj Temple, excavated into a rock face and dated to the early medieval period. It’s simple in style and modest in size, but it contains an inscription that made this entire trip inevitable. In that inscription, the circular symbol “0” appears as a true numeral, often cited as the earliest stone inscription in India that uses a round “zero” in a way we’d recognise today. The “0” shows up in the numbers themselves, in a very practical context: the inscription records details like garden dimensions and daily offerings, and the last digit in figures such as 270 and 50 is written as that unmistakable little circle. It’s fitting that zero enters the historical record not through drama, but tucked into an administrative note about measurements and garlands.

Zero is one of those ideas that looks small until you realise it quietly rewired civilisation. It makes place value work. It makes arithmetic scalable. It opens the door to algebra, calculus, and eventually the kind of computing that runs on strings of zeros and ones. The Indian numeral system and mathematical methods travelled westward largely through the Islamic world, and by the time Europe properly absorbed them, they became part of the toolkit that helped power later scientific and commercial leaps. I could go on, but I’ll save it for in-person conversations if anyone wants to accidentally start a history discussion at an AFF event.

Two links for anyone who wants to go down the rabbit hole:

Brahmagupta - Wikipedia

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/sep/01/hidden-story-ancient-india-west-maths-astronomy-historians

One small complication: the inner sanctum that contains the inscription was locked. Not one to be deterred, I marched up to the office, found a responsible adult, and convinced them to come down and unlock it. And there it was: the gloriousness of finding nothing, preserved in stone, behind a door, in a fort, in a fog, at 7:30 in the morning. Perfect.

"270"