Transnistria

Transport options: If entering from Ukraine, bus or train from Odessa are possible options. I would recommend train for smoother border control, although those only run three times a week. Within Transnistria, minibuses are the main way to get around, though there are some intercity/intertown trams. There are buses to many cities within Moldova, with most services being to Chisinau or Komrat (the capital of Gagauzia, a Russian-speaking region in southern Moldova).

There is no telecoms company here that I’m aware of, so if connectivity is important to you, get a suitable SIM card before you head over.

The cities I visited, Tiraspol and Bendery, are both pretty walkable and you probably save time and get to see interesting sights more than if you take a tram or a bus to get around the city.

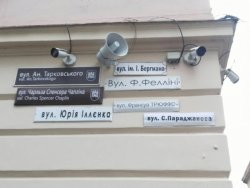

Language: Russian, Romanian (they call it Moldovan), and Ukrainian are the official languages, but Russian is the most-known and the interethnic one so it's what you'll hear 99% of the time. Romanian can be found on plaques used for commemorative or official purposes, albeit a Cyrillicised form of it (Moldavian was originally written in Cyrillic, and Transnistria being Transnistria, they had to preserve that).

Below is my impression of Transnistria, based on what I saw out and about and in the museums, and my general knowledge of this region. I’ve done some research to corroborate my notes, so have tried to keep it as factually accurate as possible but there may be mistakes and the interpretations of those facts are mine. Also, it was difficult trying to make this orderly while covering everything, so apologies for the turbulence.

"Welcome to the capital of the PMR – the order-bearing city Tiraspol"

PMR - Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic - is the Russian name for Transnistria.

I don’t know what order/s it’s referring to.

I arranged a transfer from the train station with my hostel host, which I would recommend because the border agents ask a lot of questions about who you’re staying with.

Transnistria had been part of the Russian Empire from ~1806. After the revolution, they became part of the Moldavian ASSR, an autonomous republic of the Ukrainian SSR. The MASSR included parts of what is now Ukraine, and the original capital was the city of Balta near Odessa, but the capital was soon shifted to Tiraspol. The quality of life increased a lot: healthcare (in my trip notes I wrote that a lot of people were dying in hospitals prior to the Soviet period, but didn’t record what they were dying from), education, the economy all improved. The MASSR also collectivised and industrialised rapidly compared to the rest of the country.

The May 1 Factory, a canning factory founded in the early 1930s.

Given the overall increase in quality of life, and Tiraspol’s relevance as the MASSR’s capital, it’s no surprise that it’s generally looked back upon fondly. I'm not, however, sure how the Holodomor fits into their assertion that life was better during that time. As they were part of the Ukrainian SSR, they also suffered during the famine. Even if they had the

lowest total deaths and the second-lowest deaths per 100,000 rate among Ukraine's regions, a toll of 68,000 people is nothing to sneeze at. (I have not evaluated the method that paper uses. There are some Ukrainian academics who include the future children who would have otherwise been born in their Holodomor death counts. My main reason for selecting this study was that it breaks it down by region.)

In any case, they insist that 1924-40 were Tiraspol's glory days. In 1939/40 the Romanians captured Transnistria and incorporated it into Romanian-occupied Bessarabia. After the Soviets liberated Bessarabia later that year, they formed the Moldavian SSR – with the capital of Chisinau.

That would’ve rankled. Transnistria had been administered by Russia for a long time; they spoke Russian, they had ethnic Russian populations, and since they’d only been part of Romanian Bessarabia for a short while, they’d been spared most of the Romanianisation that had occurred. Chisinau was a relative upstart. Yet, nevertheless, Chisinau was chosen as the capital and even though Transnistrians probably still enjoyed a higher quality of life, they have yet to get over that insult. The 1990 formation of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic can, I quote from the history museum, “be regarded as the restoration of historical justice”.

Note too that this was 1990. The Moldavian SSR seceded from the USSR in 1991. This territorial dispute pre-dates the present-day Republic of Moldova.

The House of the Soviets, currently used by their legislative body, iirc.

I'm not going to post more Soviet-throwback photos since we've probably all seen them, the hammer and sickle emblems everywhere, the black-and-red colour scheme, the mosaics and the lack of advertisements. (I was also able to watch YouTube at the hostel without any ads, although was too tired to take full advantage of that.) Partly because of the photo limit, but mainly because I think it’s inaccurate to think of Transnistria as just a ‘Soviet’ place and to fixate on that. Although of course that’s the key attraction, its history extends way beyond that.

"To A. V. Suvorov, the founder of the city. 1979"

The main square is Suvorov Square, not, say, Lenin Square, and in fact it seemed to me that the Suvorov statue was the more important monument. It stands opposite De Wollant park, named after the Flemish engineer who served in the imperial Russian army and went on to play a pivotal role in the building of Tiraspol fortress (and Odessa – he was one of the four founders of that city).

In the late 1700s the Russian Empire came along, Suvorov founded Tiraspol in 1792, the place developed economically and politically a bit, was used as part of the line of defence against the Ottomans, who had been controlling Moldavia for a while. This is a key point of Transnistrian identity, such as it is. They are very proud of the role they had during the Russian Empire's days. To understand this better, I went to the city of Bendery, a short marshrutka ride away from Tiraspol.

I accidentally got off a few stops early and had to walk the rest of the way. The terrain's sometimes variable, but it's a main road and the distance between the two cities is pretty small so it'd probably make for an interesting walk to go the whole way.

"The city of Bendery, founded in 1408." This bus stop, the one I should've gotten off at, was built during Soviet times and there are some awe-striking examples of mosaics inside.

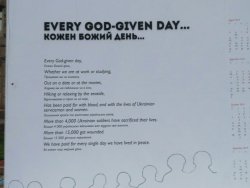

Bendery has a memorial park dedicated to the 1992 war against Moldova, and especially commemorates the 'Bendery tragedy' where, in the midst of peace negotiations, the Moldovan army attacked the city.

One of the tanks used by the PMR during the war.

Bendery's main tourist attraction, however, is the fortress. This was built in the 16th C by the Turks - you can still see Arabic on the walls. During the Great Northern War, King Charles XII of Sweden fled to Bendery and sought asylum from the Ottomans, who were at that point not engaged in the war. This they granted, eventually moving him to a nearby village as his little community of Swedes was growing too big for Bendery. Here he would rule Sweden for three years. He convinced the Ottomans to join the fight against Russia, which they did, but the two countries made peace eventually. Charles was not the most gracious guest and after a build-up of grievances and rising frustration over his agitating for the Ottomans to rejoin the war, a fight broke out and he was arrested. He lost four fingers and parts of his ear and nose, but apparently never regretted because he'd rather let them "consider me crazy than cowardly!"

The inside of the fortress. It seemed very old, with dingy cave-like rooms and collapsed staircases. The displays have English translations but, well, the other visitor who was there, a Serbian man in a France soccer cap, asked if it was just him or was the English dreadful, almost incomprehensible even. It wasn't just him.

The result of the Great Northern War was that the Russian Empire began its rise and the Kingdom of Sweden, hitherto one of the most powerful European states, its fall. And for three years that king had been just outside Bendery.

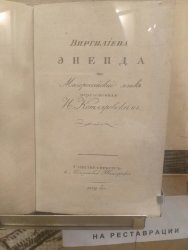

The fortress would bounce back and forth between Russia and the Ottoman Empire during three Russo-Turkish wars. Pushkin and Kotliarevsky (the one I mentioned earlier, who wrote the first text in the modern Ukrainian literary language) served at Bendery. Aivazovsky fought here. Kutuzov served with great distinction here - and he would become nothing less than the man who led Russia during Napoleon's 1812 invasion.

So, my point is, this region is steeped in cultural and historical significance, and they care about that. The Bendery fortress is the only tourist attraction out of the ones I went to that had English translations, even if they were nigh on incomprehensible. They care not only about the Soviet times, but also about their significance as part of the Russian Empire.

The view from the fortress over the Dnestr. The bridge is the one that joins Bendery with Tiraspol. At night the trusses light up, one set in the Transnistrian colours and another in the Russian colours.

I think it’s also inaccurate to say, all right then, they’re obsessed with Russia, which is how some people interpret it. There's the Ukraine connection, for one. They were

part of Ukraine during their Soviet glory days; at some points in time, ethnic Ukrainians made up the majority of the population. The Ukrainian army helped liberate them from Romania and also provided assistance in the 1992 war. The Transnistrian national university is named after Taras Shevchenko who, as I might have described earlier, was a vocal anti-imperialist and is

the figure for Ukrainians today who want to resist Russian influence. If you go to Ukraine, you will see Shevchenko everywhere. There is a warmness towards Ukrainians, who do, after all, make up about 1/3 of the population today, Ukrainians are an integral part of Transnistria, and this warmness is not found in the 'Little Russian' attitude of the Russian Empire or today's rhetoric.

Yes, they are obsessed with Russia, and yes, in their referendum they voted not just to secede from Moldova but to join Russia, and their politicians pretty much view it as a foregone conclusion. Several websites belonging to the republican/municipal governments use the .ru or .рф extensions. But there is a part of the Transnistrian identity that does not fit in with Russia's.

Another case in point: Transnistria's relations with the Moldavian Principality. It had always been a frontier relation, some parts under Moldavian influence, some nominally Moldavian but administratively Turkish, and a large portion belonging to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Regardless of who ruled the region, Transnistria initially had a significant Moldavian ethnic presence, which it still does but to a lesser extent, and it seems that Transnistria actually feels itself to be the last bastion of true Moldavianism, decrying Moldova’s increasing cultural and linguistic union with Romania, and the threat of a political one as well. Transnistria is, after all, the Pridnestrovian

Moldavian Republic. They respect Moldavians, just not Moldova.

The train station, with the Romanian word 'gara' written in Cyrillic.

What I want to say is: there is so much more to Transnistria than what tour companies or most travel bloggers will talk about. After my short time here, I really began to see Transnistria as a separate country because it's run like one and it feels like one. The uniqueness of its identity is based on the fact that it doesn't have a single story-line, it's a mix of histories, cultures, and ethnicities.

The idea of its independence became so natural to me that when I ran into issues at the Moldovan-Romanian border and they asked about my entry into Moldova, I told them I'd taken the bus, because I had taken the bus from Tiraspol to Chisinau. Things might have been different if I'd said it was the train from Odessa. More on that in the next post.

The main lesson for me from this trip was that there are so many connections to be made that extend beyond time and geographic borders. Which I guess we all know intuitively, but it's still delightful and stimulating to experience. I mainly travel to learn, and actually came back to Australia more exhausted than I'd left.

Thanks for slogging through my extensive ramblings. I'll have 1-2 more posts with some miscellaneous stuff, but this is the main content. Let me know if you have any questions, and please share thoughts/observations from your own experiences if you've had the good fortune of visiting these places!